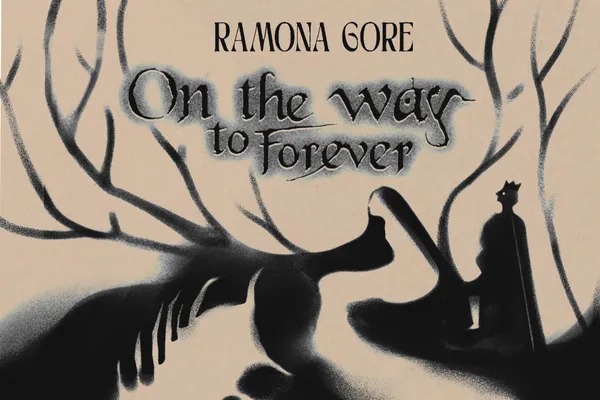

🪱 On the way to forever

by Ramona Gore

A suit from the Cavendish Mining Company goes through Remanufacture and Reclamation.

Jenny Choong-Uche’s motley was smeared in grime, mineral oil, and viscera. It was the latter that marked it for my attention in Remanufacture and Reclamation.

Of course, only the dustiest-footed of the zeroes wore unadulterated Cavendish Mining Company issue: the cerulean suits (don’t let them hear you say “blue”, always cerulean); the cheap seals; the tools bought in bulk from suppliers competing on cost, not quality.

The drones in Buying did not have to depend on their tools not fragmenting in hard vacuum or the seals of their suits not cracking after multiple heating and cooling cycles. The phrase “within acceptable tolerances” was said with a grim smile at many a wake.

Rich rockjacks could afford better, of course, suits in the colours of their sponsor nation, keiretsu, or abantu, titanium reinforced carbon-fibre frames, synthetic-diamond tipped drill bits and fresh, flexible seals.

Jenny’s suit had been Reclaimed at least twice, judging by the weld scar across the abdomen, and the vacuum-safe stitching and glue job across the thigh of its degraded red fabric. Its seals smelled slightly of pork, the product of the Pigman’s work no doubt, the rendered-down radioactive denizens of the hydroponic filtration ducts providing a cheaper, if less effective, alternative to synthetic products.

I had met Jenny once, at a funeral of course. She claimed to be a cousin of the Dr Choong-Twumasi, and I supposed it was possible. I had grown up with that accent, learned English from it, first from the cartoons Cavendish made as soft-power propaganda, and later from recordings played in science classes and museum halls. And London, now, was the sort of place that zeroes would come from. Venice North, they called it, the whole city crumbling into the Thames estuary, the tidal basin sucking the bricks off buildings long submerged, slums clinging to the roofs of tower blocks, prison hulks repurposed into housing for a new class of inmate.

If you live in a floating slum, then a floating cell in space wasn’t that bad.

At least up here you had the hope that you would hit a mineral seam ripe for the market and become wealthy beyond your wildest dreams. So long as you didn’t read the small print in your contract of course.

That’s what killed the hope for me.

I found the damage to the suit easily enough. A damp sponge cleared off the blood and filth, and there it was, a clean puncture. Easy enough to fix.

I unscrewed the helmet, the visor caked in dried spit and vomit, chunks of undigested plant-protein and indifferently made jollof rice clouding Jenny’s last view.

Her ashen face showed the panic of those final moments.

With the helmet off I could release the rest of the suit, emergency toggles now accessible with the right tools. Or a bamboo chopstick with a notch carved into it.

I found more blood than I expected pooling in the boots as I peeled the suit off the limp frame within. The hole was a through-and-through, a pellet of stone flung loose from the mining equipment she’d been riding escaping at a terminal velocity through her body. At least that’s what the company would say, if anyone bothered to ask. It could have been a loose washer, a bolt, a rivet, any metal item warped by cycles of cooling and reheating and jarred loose with impersonal venom.

I drained the blood into the drains for Recapture, and marked the suit for steam cleaning before Repair. If the next occupant was lucky there would be no residue trapped in unseen folds.

Repairs booked, I could move to Remanufacture and Reporting.

She didn’t weigh much when laid out on the table. Naturally slight, like most of the zeroes, even before the privations of low gravity and her recent exsanguination.

Algo gave me the weights and proportions. The usual amount of water for someone in Remanufacture. Phosphorous at 1%. Potassium closing on 1%, a rare enough mineral that it had some commercial value in the circular economy, destined for potassium iodine tablets for illusory protection of space dwelling thyroids. Magnesium we had in abundance, sifted from the slag of a hundred thousand asteroids through the belt, so her own mortal weight added little to her tally.

I hoped against hope, but as ever the screen churned out a red notice, net indebtedness. The zeroes never cleared a margin to send anything home to a mourning family beyond a 144 character death notification and a link to further impenetrable legalese.

“From earth we come, to earth we return,” I told her.

The processors swallowed her without a murmur.