🪱 On the way to forever

by Ramona Gore

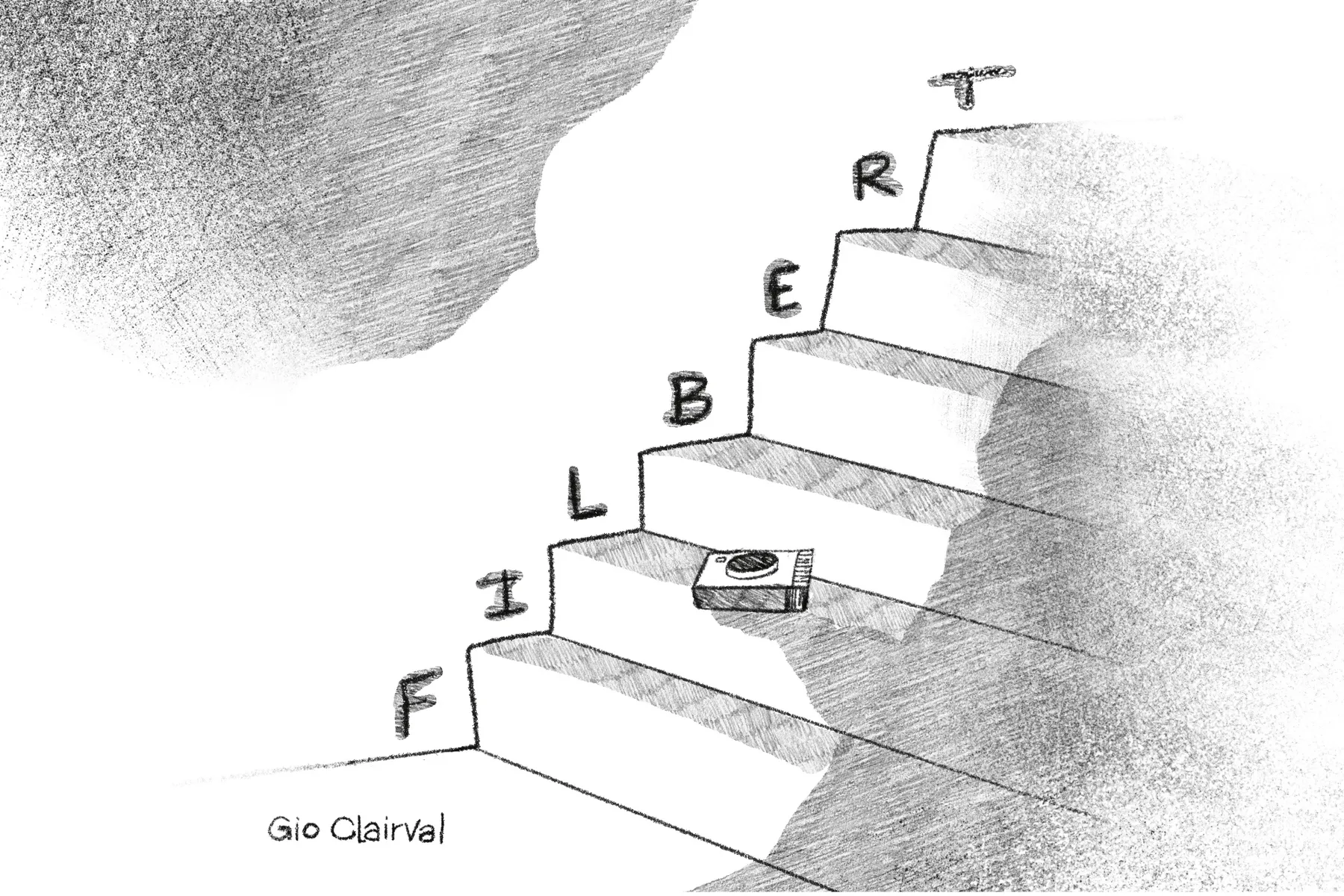

by Gio Clairval

The first time I saw Filbert, I was adjusting the settings on Papa’s old Leica. He’d finally trusted me with that nifty camera—it was like being handed the keys to a kingdom. That Sunday, my fifteenth birthday, I climbed higher than usual to capture the valley as it stirred beneath rollers of mist. I’d send my best pic to the professor. Maybe she’d pick me for the exhibition next Friday.

At school, I existed in the margins: the girl who spoke about obscure things, who noticed patterns others missed. A ghost in reverse, visible to everyone, understood by no one. Here, through the lens, the world sharpened; my vision made real, a part of me normal people might grasp. I existed for everyone when I held a camera.

Then I saw him though the lense.

In a pocket of shadow under a hazel shrub.

Just a flicker at first, a ripple in the dark. A boy, no taller than my hand, standing on a flat stone, watching me with too much awareness for something so small. He looked like a human. Except for his edges, blurred like a photograph in motion—like he wasn’t entirely there. His tiny face tilted up and I caught the glint of dark eyes staring at me with curiosity, as though I were the oddity, not him.

The moment I pushed the branches aside and sunlight touched him, he vanished—as if he couldn’t exist in the light.

I should have left it at that. Pretend I imagined it. But when I started down the mountain, he followed. No footsteps, no sound—just flickers in the corners of my vision, slipping from shadow to shadow. When the sun went down, he stepped into the moonlight. I framed him again: a blurred silhouette, wavering against the grass and shrubs—half there, half not.

I snapped a shot of him.

Back home, there he was, on my bookshelf—until I switched on the lamp.

“Where are you?” I called.

I turned off the light. There he was.

“What are you?”

“I don’t know.” He stepped closer to the edge of the shelf, his small form swaying. “Nobody looks at me, or maybe they only remember me for a short while.”

My hand moved toward the light switch. He jerked back, pressing himself against my copy of No Longer Human. “Please… don’t.”

He told me he could only exist in darkness and paced the length of my bookshelf. His voice was quiet and weightless. He smelled like damp earth.

He didn’t have a name. I told him I’d call him Filbert, after the hazelnut shrub he’d been standing under when I first framed him with my Leica.

When I developed the photos in my tiny red-light closet, he was nowhere to be seen.

“Are you a ghost?”

He stopped to face me and his blurred features shifted into what might have been a smile. “No. But I think I know what ghosts feel like.”

“That makes two of us. Will you stay?”

He sat down on the shelf’s edge, legs dangling. “Only if you keep the light away forever.”

“I can’t do that.”

“Sorry, then.”

The last thing I saw before I fell asleep was his shape, stretched long against my wall.

Then morning came, along with Monday.

And he was gone.

At school, I watched girls in clusters, couples in hallways. A universe I couldn’t access. I pressed my back against lockers, arms wrapped around my textbooks.

That night, when I turned off the lights, Filbert appeared, smiling.

He stood at my darkened window, one translucent hand pressed against the glass. “Can you switch off the sun in the morning?”

“I’m afraid I can’t. But I can keep the shutters closed.”

I moved closer, studying the fine details of his face: sharp cheekbones, a mouth that curved down at the corners. He didn’t trust me.

Morning came, Papa found me sitting in the dark, arms around my knees. “What’s up with you?” He crouched beside my bed, his lined face creased with worry. I turned away from him, shoulders hunched. He looked concerned, but I shrugged it off. Said I was fine.

The day was a blur I drifted through it waiting for the night to talk with Filbert.

When I got home from school, he was the size of a child. I didn’t know what to think. We sat cross-legged on my bedroom floor in the moonlight streaming through my shutters. I told him about myself, the invisible patterns I saw in things, the way I saw the world differently. As I spoke, his eyes never left mine, nodding along. That’s how I knew he really understood me.

On Wednesday, I wore sunglasses indoors, and black clothes. The school’s cafeteria neons were too bright, the constant chatter like needles in my ears. I walked away from the others, head down, shoulders curved inward.

My phone rang for the first time in months. My photography teacher said, “The arts department selected your mountain sunrise for the exhibition. Opening night is this Friday. I know it’s a bit short, but I’m counting on you. I’ll see you there.”

Yay me! Yay! Right?

Instead, my gut twisted. I sank onto my bed, phone still pressed to my ear. I thought of the hours under fluorescent lights, voices echoing off gallery walls, the smell of wine and perfume—all of it weighing down on me.

But I should go.

“There’s an exhibition Friday,” I told Filbert. “They picked my photo.”

He stood near my dresser now, nearly my height. Even in the shadow, I could see the tension in his jaw. “Don’t go. If you talk to people, you'll forget about me.”

“Never!”

He stepped closer, and the temperature dropped around me. His eyes—darker now, more desperate—searched my face. The silence made me hungry for his words.

Friday night arrived. Outside my window, Papa started the car. I stood at my bedroom door, hand on the knob, wearing my one lovely dress. My reflection in the dark window showed a girl caught between two worlds—the fabric beautiful against my skin, but my face pale.

“Please,” Filbert said.

He was taller now. We were eye to eye. His features had sharpened, become more defined, more real.

I pictured my work on the wall, people stopping, smiling at me. For once, I would belong. I saw my father, proud, waiting for me to step into the light. But I also imagined the noise, the crowd of bodies, the way sounds would bounce and multiply until I couldn’t think.

Filbert’s voice curled into my ear, soft and urgent. “I don’t think I exist when you’re away.” Chill radiated from his skin.

I looked through the window at my father sitting in the car. The dashboard lights illuminated his face. He lived in the light, like everybody else.

Filbert stood perfectly still, waiting.

At the exhibition, I’d be displayed like my photograph. Framed, admired, but alone.

And here, for the first time, I wasn’t alone.

My hand fell from the doorknob.

When Papa honked, I knocked on the windowpane and shook my head. He met my eyes through the glass, and then looked away. He sat there for a long moment before getting out of the car. He didn’t come to my door. He knew why I couldn’t go.

I’d worked hard for months. Got the photography teacher’s attention. I touched the Leica on my dresser. My fingers felt carved from air, too heavy to lift anything but shadows.

I always preferred being alone.

So I picked up the camera. Looked at Filbert through the lens. His image was perfectly neat.

But my reflection in the mirror wavered.

I let my hand hover by the switch. It would be so easy. A click, a spark, and the dark would shatter. Filbert would disappear. I’d call Dad. “I changed my mind. Let’s go.”

I should go.

Instead, I turned toward Filbert. He stood there, head bowed.

“I’m not going.”

When he moved toward me, I could see we were the same height now. When he reached me, his fingers—cold, but solid—intertwined with mine.

“Forever,” we said together.

In the darkness, I could no longer tell where I ended and the shadows began. We stood facing each other, hands clasped, and I watched as the edges of his form began to blur again, but this time, so did mine. We bled into each other like ink spilled in water, unraveling in slow, endless loops. Boundaries thinned, stretched, and forgot themselves.

A breath, a ripple, a shift in the air. I felt my own edges soften, my own form becoming translucent. We moved together, two figures becoming one shadow against the wall. I was already less myself, already more of something else.

as witnessed in the viral video “Fat man pushes old woman for free donut,” viewed over six million times on YouTube