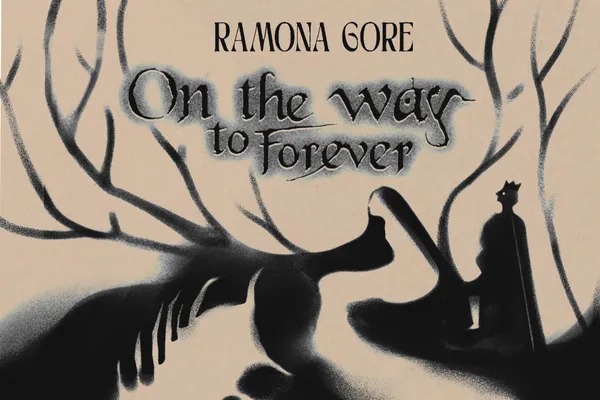

🪱 On the way to forever

by Ramona Gore

Start your pretty good blog now!

Get 20% off your first year with code: FOOFARAW20

“WE! WE! WE! WE! WE! WE! WE! WE! WE! WE! WE! WE! WE!”

It ends with an unsold Queen, this carnival.

She’s the only one that refuses touch, she hums to herself smugly, so the chase of fingers must cease; the revelry, in this finale, will be realized in her regal gaze. No one may hold her, choke her, fuck her again. Free at last, the Queen surveys the Carnival’s corpus, captured by her fully clothed, wholly untouched corpse. Time finds no terra firma when work goes wayward—when the only wage is the waging of unholy war. How the Queen’s coffer organizes alchemy: toil into joy, struggle into frolic. This court of royals and reverends devolves into foolery, revolving in tactile diversions over the ruins of the 9-5. But before the Queen’s pantied tush perches on a throne of trash, after her thonged cheeks grow numb on a screeching subway, she arms herself in cloth sacrosanct.

Or her Lady-In-Waiting does, his smooth fingers lacing her straitjacket, buckling her collar, locking her chastity belt. He doesn’t mean to lick her skin, that innocent junction where wrist meets hand, and ahead of that fortuitous fumble, he gossips with the other Ladies-In-Waiting, trading culture instead of finance, playing petty in place of pompous. Stocks are a primitive pastime, debt is a darling relic, and he concerns himself with neither, embracing mayhem, not market. He feels a real girl-belonging in his lipsticked skip around the maypole, giggling as ribbons and legs tangle together. On the grass that once was, will be asphalt, the feminine flock forgives his phallus and teaches him to ride the Four Horsemen; there, a knighted heel leaps over his spine.

That Knight seeks to escape the rows of gluttony, where black pudding stains her loose armor, deseeded berries woven beneath her helm and across her thin plaits, rotting apples stuffing her gambeson to slight blades. This topsy-turvy fun bears no ratings—friendly not to families but to fools, especially those immature. Who could blame the Knight for indulging? But if her mommy knew she had gorged so many sweets! She’d never again wield her shiv, she’d never again chant her potty-mouth, she’d never again know the Bishop’s hand under her chin telling her to look, now, be a bad boy, and look away from the carousal.

Even trash transforms glorious with the proper, improper perspective, and the Bishop forgets his shame as he does his hygiene, stinking of mundane waste—leftovers smeared across his chest, shards of plastic speared into his arms, maggots and flies chewing his feet raw. Adorned in divine filth, the Bishop leads a sermon in lechery, a mitre of rats chewing their liced hair as they bless the privates—the flick of holy water is by no means sufficient, a kiss of Judas for them all, no matter erect or budded or some transgression in between. They ache in the lovely shame of skinned knees. They answer questions with questions of questions. They adore their worshipers, the Bishop, elated to sanctify what’s soiled instead of wasting its glory.

“WE!” The only pronoun known.

Needles emerge from limbs, a blockade of bodies—watermelon red smokes the air where black cats fly—weeds sprout from break-your-mother cracks up to the traffic lights—puppets watch on from stilts, gods of festival—books bound unbind wild—spray paint bathes brick and asphalt, seeding color in corporate.

“WE!” The last pronoun common.

The first of the Bishop’s acolytes, curious and cast out, hunts for more than lips, plunges into the well of consecration, and this Demon is welcome, here, to want that which he may not. The vice and virtue he once discerned find no difference amidst hell’s paradise. He is hailed into cavities and craters and chasms until he has orchestrated sin itself in a crowd of rakes and casanovas, spreading the word of under instead of above with zines of Daemonologie—how to greet the good and dead with the bad and alive. His tactile tutelage, endarkening those he once enlightened, profanes profound after the Demon’s tryst with the Princess, whom he offered a pomegranate.

The Princess had never had a pomegranate, had never understood its hard shell full of seeds, juicy and sully. She lived a simple life, will live a simpler life, and now she knows a bountiful one, where smiles are abundant and wealth is unhoarded, where space is made not for locked doors and paved roads but mirth and merry, carnal desires spread across a made city unmade. If there are no homes there may be none homeless—if there are no laws there may be none lawless. The Princess finds this nirvana when she pulls the first card from the tarot pile, and how the Fool laughs!

Spreading news of the feast, cards of the carnival, the Fool swaggers her wide hips, his bulked arms, their pursed lips, and plays tricks on his companions, their lovers, and her friends, making light of the culture’s crimes, of which the Fool long ago indicted. On the tracks of that rumbling train, the Fool was not a Fool at all, but a man in blue, glaring at the one who called herself Queen, fully unclothed, picking up hungry customers at rush hour.

It starts with an armed cop, this carnival.

“WE—”